Uncontrolled confounding

Uncontrolled confounding is the affect of a third variable that is related to the two variables under study. This relationship can alter the apparent relationship between the variables under study. For example, if one studied the relationship between reading ability and body weight among grade school children, there is no scientific reason to expect increased body weight to cause improved reading ability. However, such a study would certainly find a strong association. The reason is a major confounder - age. Increased age causes both improved reading ability as well a greater body weight. Failing to account for the confounding effects of age would produce a misleading association between body weight and reading ability (and possibly lead to some interesting dietary interventions!). Confounding is such an important potential source of research error that is discussed in greater detail in a special section at the end of this lesson.

Confounding - What is a Confounder?

Assume you are investigating the relationship between exposure E and disease D. Let us also assume that these two variables are related with a true relative risk (RR) of T. Remember, study results that deviate from T increase the likelihood that you will make an erroneous conclusion (false positive or false negative). A confounder is a variable which, if you don't do something about it, will cause the observed RR to deviate from T through a very specific mechanism.

The mechanism by which a confounder causes a deviation from the true RR is by being both:

1. A risk factor (cause or indicator of a cause) for the disease in question, and

2. Associated (causally, by chance, or otherwise) with the exposure of interest.

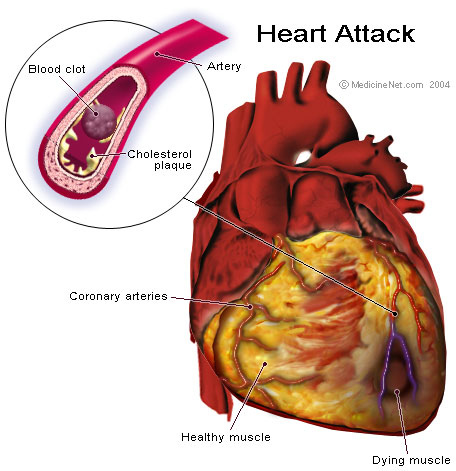

Let's look at some examples. You are examining the relationship between heart attacks and a sedentary lifestyle. You interview a number of people who recently had heart attacks and a similar number of controls without heart attacks. From your questions, you determine whether they have had a sedentary lifestyle during the last 6 months. You find that those with heart attacks were twice as likely to be sedentary, suggesting that a sedentary lifestyle might increase one's risk of a heart attack. Can you think of a potential confounder? How about age? It seems plausible that age contributes to a heart attack (risk factor for the disease) and it is also plausible that age could be associated with a sedentary lifestyle (older people are more likely to be sedentary). The observation that those without heart attacks were less likely to be sedentary could simply be because people without heart attacks are younger. In this case a conclusion that a sedentary lifestyle increases the risk of a heart attack would be in error (false positive).

You are examining the relationship between the risk of accidents and working in one of two manufacturing processes within a plant, one of which involves a large number of stamping operations. You find that the rate of accidents (per 100 employees) is about the same at the two processes and you conclude that the stamping operations are no more risky that the non-stamping operations. However, it is plausible that, for whatever reason, women may be less likely to be injured than men performing the same task (being male is a risk factor for injury). If there are more women than men in the stamping operation, this may be masking the association between the operation and risk of injury (stamping may appear no more risky simply because more females are involved). If gender were acting as a confounder in this way, you would have made an error concluding that stamping is no more risky (false negative).