Learning Objectives:

After successfully completing this lesson, you should be able to:

1. List and describe various types of bias in research studies.

2. Identify types of bias given a research study.

Error - A Bad Thing!

Most research is intended to better understand a problem so that is can be reduced or eliminated. If we have errors in our research, it will slow our progress - and may even make things worse!

Consider a research study on how high school students' attitudes about tobacco companies relates to their smoking habits.

The research findings might suggest one of the two following outcomes:

- Attitude influences smoking behavior, or

- Attitude does not influence smoking behavior

If we believe #1 is true, then we might seek funding to include information on tobacco company deception in our anti-smoking program. If we believe #2 is true, we will drop the issue and move on to something else.

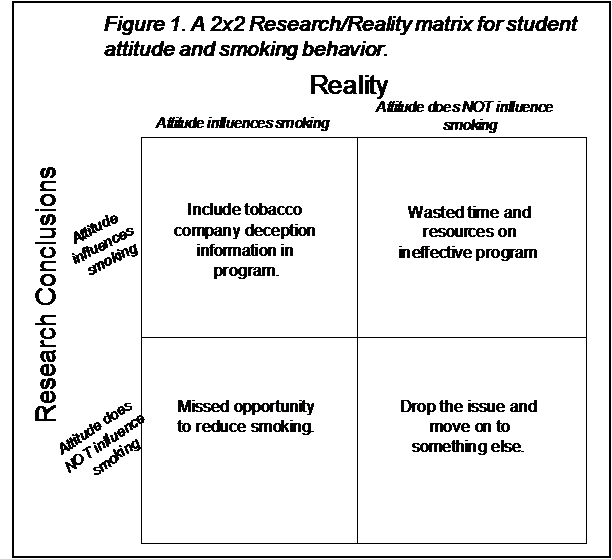

Of course, believing something is true doesn't make it true. Reality and our research findings may or may not agree. One way to view this is pictured in Figure 1.

In the upper-left box, both reality and our research findings agree that attitude influences smoking behavior. We can be pleased when this happens because we have a better idea how to go about reducing smoking. In the lower-right box both reality and our research findings agree that there is no relationship. We can also be somewhat pleased with this since we now know that we can use our time and money on other, more productive interventions.

However, the upper-right box is a problem. Our research suggests that attitude influences smoking but it really doesn't. This is a problem because we may now spend time and money on developing an intervention based on tobacco company deception, even though it will not have any effect on smoking. This is time and money that could have been spent on effective interventions. Similarly, the lower-left box is a problem because attitude really does influence smoking behavior yet our research suggests that it doesn't. In this case, we have missed an opportunity to reduce smoking. A number of lives may end prematurely because we failed to find an association that was really there.

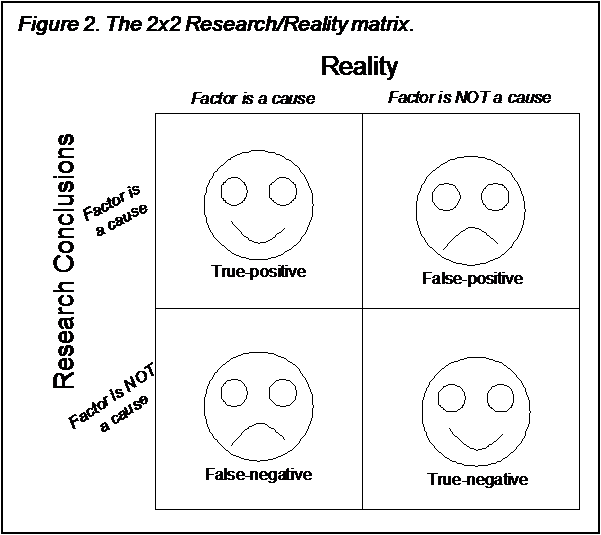

We can generalize this in Figure 2. Whatever the outcome of our research, we would like to end up in the upper-left or lower-right boxes. A research result that shows an association is called a "positive" result, similar to a blood test that shows someone to be "positive" for a disease. Thus, we call the upper-left box a "true-positive." Similarly, the lower-right box is a "true-negative."

On the other hand, the upper-right box is a "false-positive" because the study results were positive, but the reality is something different - that is, the results were "false." Similarly, the lower-left box is known as "false-negative." There is always a price to pay for false-positives and false-negatives. The price of a false-positive is generally wasted time and money on an ineffective intervention. The price of a false-negative is a missed opportunity to reduce a problem. In some research, these prices might be quite small. In other research, where people's lives depend on the outcome of the research, the price can be extremely large.

Research error is what causes us to end up either in the false-positive or false-negative box. Thus, it is important for us to understand the sources of research error and how to minimize them.